Jim Ross

Our Living Remains

Our kids tell us they don’t care whether there’s an inheritance when we die. They just want us to get rid of our shit before then. Friends tell us they’re hearing similar messages from their kids too. “It’s not that we don’t love all your shit,” these kids say. “We do, but only because we love you. It’s your shit, though, not our shit. So please disavow yourself of the notion your shit someday will become our shit and we’ll be happier than pigs in shit. If there’s something you think we should value, show it to us and tell us why we should care. Tell us the stories we need to hear so we can share the love. Otherwise, we love you, but please, please, just get rid of your shit.”

A year ago, my wife Ginger and our son Alex began the process of clearing out our basement and attic. Now and then, after dumping a stack of boxes alongside my desk, 33-year-old Alex would say, “You need to look over this stuff. Otherwise, it’s going out.” So far, I haven’t given the undertaking my undivided attention. Part of the problem is that what Alex calls stuff I consider relics, varying along a spectrum in their sacredness. Indeed, these relics—the souvenirs that tell the stories of our lifetimes—constitute our living remains. They’re “our stuff” in the best Steve Carlin sense.

I say it’s too soon to talk about a major purge. At the same age—right after my Dad retired—Mom and Dad downsized to a smaller house. Like the crème de la crème, they still had their stuff de la stuff. Satisfied with how they’d dealt with stuff, Dad then became obsessed with the notion, “We need to do things to make time go slow.” Time was going too fast, he said, and the only way to slow time down was by “constantly challenging yourself.” He tried to attract fellow travelers by explaining, “It’s just like the first time you go on a trip to a new destination. You experience the newness of everything and time goes by slowly. When you travel to the same destination again, you pay less attention, so the experience goes faster. Once it becomes routine, time whizzes by, you lose your ability to experience newness, and you miss nearly everything.”

Almost two decades later, Mom had a stroke, and Dad became her sole caregiver. He said it felt like he “was working both ends of the street.” He suspended his experiment in making time go slow, stopped taking time to open the mail, stopped doing his sacred New York Times crossword puzzles, stopped going on walks, to church, and to their choral group. He chained himself to the house because he wouldn’t entrust Mom’s care to anyone else.

Sixteen months later, a week after Mom’s and Dad’s 60th wedding anniversary, the morning after Valentine’s Day, as Dad hoisted Mom’s wheelchair into the car to transport her to a doctor’s appointment, his heart gave out, and that was it. His last words were, “I’m okay. I’m not in pain.” He’d long planned to make his exit exactly like that—he’d mentally rehearsed it—because the last thing he wanted was to linger. Simultaneously, we inherited mom and all their stuff.

A year after Dad died, while Mom lived comfortably at an assisted living facility, Ginger and I, along with my brother Bill and his wife, visited their house in anticipation of putting it up for sale. Vacant for a year, it still smelled like a mothball factory. The relics of their mingled lives, well-kept and organized, defied apparent space limitations: It rapidly became clear Mom and Dad knew their stuff.

Sometimes, we came upon a true find, like Dad’s “pop’s” woolen sweater in multiple shades of gray, size medium, circa 1929, that Dad still wore occasionally until he died. Dad insisted the tiny moth holes were signs of character, not flaws.

Boxes within boxes within boxes towered in the attic, waiting to seize the moment. Ginger remarked, “I see where you get your box collecting from.”

Tools and parts sorted into plastic drawers hung over Dad’s workbench in case something fell, fractured, and needed repair. Example: When our daughter Emily’s porcelain nightlight of a pigtailed little girl shattered into over 100 pieces, Dad had painstakingly reassembled it using crazy glue. Had I tried, I would’ve misplaced two of my fingers and glued the rest together.

A documents folder with alphabetic partitions enshrined Dad’s 1946 army discharge papers, multiple insurance policies, a letter Dad gave Mom (or perhaps didn’t) on their first married Christmas together in 1940 to apologize for how hard it was for him to say “I love you,” and a list of their wedding gifts, by donor, many still used until Dad’s death,.

A representative cross-section of Mom’s dresses from 1935 through 2000 hung in heavy plastic bags. Among them was the beige one with turquoise trim that Mom told me—when I was 12 and Eisenhower was President—she wanted to be laid out in after she died.

A leather hankie box given to Mom in 1931—the year after she escaped from foster care—filled with fancy hankies representing seven decades, still neatly ironed.

Mom’s jewelry boxes, neatly sorted: necklaces, pins, clip-on earrings, and pierced earrings. Notably, a multi-colored macaroni necklace with a note, “to my favorite agent.”

Mom’s diary from the five years before she and Dad married told her story from age 17 through 21. Of note was Dad’s telling her after they were engaged that she might consider ceasing to go out with other guys. While Dad was away during the War, Mom scribbled a confession: she passionately desired an unnamed man with whom she worked.

Thousands of donation request letters, unopened, from the day of Mom’s stroke to the day of Dad’s death, filled over 20 shoeboxes sheltered beneath the guest room’s twin beds.

Still in original envelopes and in chronological order, letters from me and my brothers Bill and Bob over the course of 35 years filled three shoe shoeboxes.

A plain tin box contained 22 letters Mom received from Sam’s parents. For years, Sam taught mom piano and me accordion at our house. Their letters say repeatedly that Dad is an honorable man of character, and Mom should forget she’d ever met their gutless son Sam. One condemns Sam for telling me he refused to teach me anymore because I had no talent or motivation when, in reality, he fired me because his wife ordered him to stay away from my family, especially Mom. Nice to learn 40 years later. A postcard shows Devizes Castle, castle where Sam’s Mum and Dad lived.

Mom’s collection of funeral memorial cards, eight inches tall, mostly spanned 1940 through 1999. Older ones, like my great-great-grandfather’s, reached back to the early 1900s. The collection came in handy, such as when my cousin, Marie, had her purse containing her parents’ memorial cards stolen, and I was able to replace them. Mom had doubles so I gave Marie originals, in mint condition.

A series of letters from Dad’s employer announced that, while Dad was away in the Army, they were awarding him his full bonus, and they looked forward to his eventual return.

I was most interested in Dad’s top dresser drawer, where he kept his balled Banlon socks, neatly arranged in rows. There I found:

- Six golf balls, each annotated and dated;

- Dozens of scattered golf tees;

- Service pins (5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, and 40 years) acknowledging his long tenure with his only employer. All the diamonds had been removed in 1990 to make Mom a new engagement ring to replace the one Dad originally gave her in 1938 that Bill flushed down the toilet in 1955 when he was five.

- A triangular stone marked “Nevile,” from a weekend Mom and Dad had spent away with friends at the Nevile resort in 1993, a year after Dad recovered from a heart attack at 77;

- A 1954 postcard of Atlantic City’s famous flying horses Dad mailed home to me in 1954 when I was 7;

- Two ace bandages, rolled, stained;

- Miscellaneous parts and screws, undocumented;

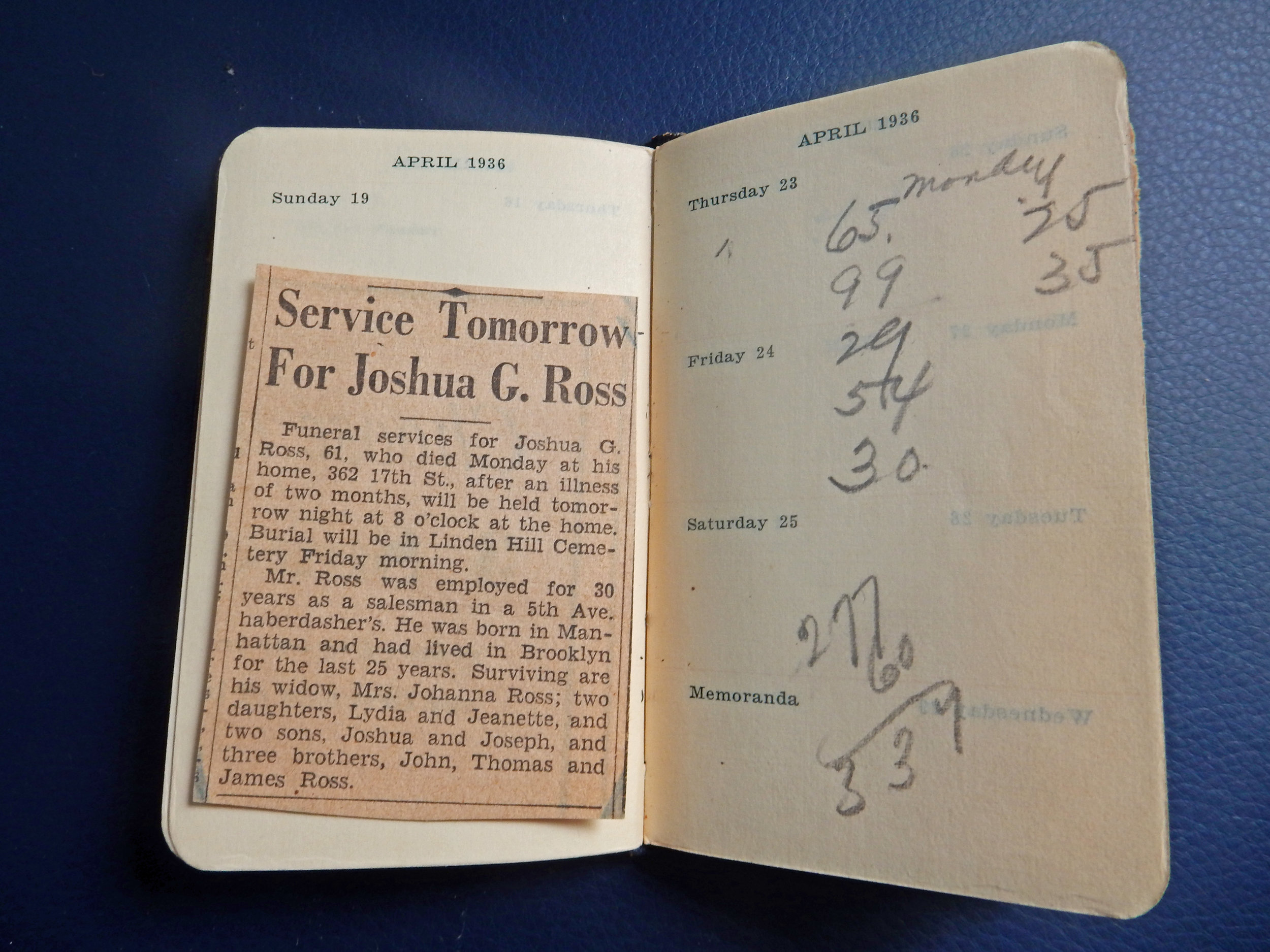

- Dad’s pop’s little black sales book, showing his daily sales at a men’s haberdashery in Brooklyn in 1936, the year he died. Sales had been perilously slow.

- A metal penny bank of a soldier Dad received as a gift at age five.

- Several pieces Dad made out of wood when he was a 16-year-old student at Brooklyn’s Manual Training High School. A ten-drawer chest for spare parts moved directly from Dad’s workbench, which he built, to mine, which he also built. A lockable box he crafted contained Dad’s dogtags, Mom’s honorable discharge as a civilian Air Warden, honor awards from their years in school, and a stunning hourglass. Why the hourglass? Had Dad created it? I doubt it. Was it there as a reminder to me, the finder?

- The tiny bride and groom figurines from the top of Mom and Dad’s wedding cake.

- A stray letter I’d written Dad in 1992 while he was recovering from the aforementioned heart attack. At the time, Alex was 9, and collected baseball cards as avidly as I collected antique postcards:

“Today, Alex and I went back again to our favorite shop. While I looked at old postcards downstairs, he looked at baseball cards upstairs. At one point, he came down and gave me a 1961 Dodgers team card: ‘You got one for me, so I got one for you.’

“After Alex went to bed tonight, he came back downstairs, holding back tears. He shook his head, wouldn’t say why, didn’t make a sound. So I said, ‘Just whisper it to me.’ Alex climbed up on the arm of the blue and white checked recliner and, holding me tight, whispered into my ear, ‘I’m not going to see much of you anymore.’ I said, ‘Well, we’ll just have to make the best of the time we do have together.’ ‘Yes,’ he said, ‘but we can’t go out to the baseball/postcard shop anymore.’ Startled, I asked, ‘Why do you say that?’ He said, ‘Because it makes time go by too fast. We have to do things that make time go slow.’”

After we three brothers divided the desirable spoils, I moved the rest—Mom’s and Dad’s living remains—to a storage space near me. Over ten years, I spent an ungodly amount of money—at least 20 times fair-market value—to hold onto Mom’s and Dad’s stuff just a little longer. Now and then, I visited the storage facility to tunnel through the dark, narrow passageways we created to inspect the goods, add even more stuff, and occasionally carry something away.

Then, in early 2012, Ginger and I bought a second home two hours away in West Virginia and moved all the stuff there. We junked half, along with an attic full of stuff that the former occupants left behind, including two box-loads of eight-tracks. I admit, I should’ve found a way to listen once to their 1963 Bob Dylan. Mom’s and Dad’s two sets of bedroom furniture have regained full use. Their sky-blue, velvet living room chairs are now widely regarded as the chairs-of-choice for holding our daughter Emily’s year-old twins, Ben and Ysabel. I still have the 22 letters, Mom’s diary, and Dad’s pop’s commission book. Well, and lots more. Our familial stuff now spreads out over two houses in two states. And recently, at a neighborhood estate sale, for a phenomenally low ransom, I rescued a magnificently carved, imposing wooden rooster that stands proudly on our West Virginia kitchen table.

I know I need to start getting rid of my share of stuff—even while we inevitably collect new souvenirs along life’s path. The bigger problem is, as Ginger and Alex sift through our familial accumulations wondering what’s worth holding onto, they keep unearthing treasures. Example: A binder of old family letters and short essays written by Ginger’s maternal grandmother, Ysabel, includes one on the importance of documenting our lives so future generations will know who we were and how we lived. In 1921, she wrote:

“There is an album of old photographs which I keep in one of my pig-skin boxes at the foot of my bed . . . The album shows photographs of great grandmother Cooper. She has dark kindly eyes but her mouth looks slightly grim. Her hair is parted in the middle and she is wearing some sort of lace cap. Her dress is shiny like taffeta and it has full sleeves and a very full skirt. How old was she then? Was she lovable and full of fun? Austere? What were her favorite books, hobbies? Was she a gracious and hospitable hostess or was the bank account a limited one and did she have to wear the shiny taffeta only “for best?” I am her great grandchild and I know nothing about her . . .”

Later in the same essay, she wrote:

“Harriet Augusta was Father’s mother. There is a photograph—a copy of a daguerreotype—of her in my album, holding Father in her arms. Her eyes are unusually large and wide apart and must have been lovely. Her mouth is rather wide and her expression a pleasant one. And yet I can only describe her as the mother-in-law Mother disliked intensely! Just why Mother disliked her is not clear to me. I know that because of Father’s modest salary at the time they were married, Grandmother Cooper was a member of the household and she apparently did not welcome the bride into the home. With a bad beginning like this, no doubt matters grew more strained with the passage of the years. Another photograph of Harriet Augusta is one taken of her as an old lady. She has the same alert, eager glint in her eyes and there is nothing to betray an unamiable or ill-natured character. Perhaps it was a matter of two utterly different personalities crowded together into too close proximity. However, it is unfortunate that there is no true record telling Grandmother’s story and she will have to go down in this record of mine as an irritating factor in Mother’s life and the only personal trait I can mention is that she hoarded dimes that Father gave to her! She kept them in a milk bottle. There is also a little laugh which still echoes through the years. When she was very old and not long before she died, Grandmother sat in her little rocking chair and every so often she gave a mocking little laugh which used to disturb Mother very much.”

Another binder contains a journal Ysabel kept from 1911 at age 17 until 1922 at age 28, wrote lookback sections for in 1934 at age 40, and assembled and flawlessly typed—all 340 pages of it—in between marriages in her 60s. Before our eyes, she recoils at realizing a young, light-skinned black woman she meets in North Carolina is barred, like all people of her race, from going to the movies. In Chicago, she breaks a box of candy over her brother-in-law’s head after he mocks the notion of women’s suffrage seven years before it became law of the land (“the candy went flying around the room, and sparks flew from his eyes.”). In Woods Hole, when her Coast Guard husband’s mission to rescue ships off Nova Scotia is extended repeatedly without notice, Ysabel fears his eyelids have frozen shut (again) and, alone with Ginger’s mother, Barbara, then eight, she axes his precious, handmade wooden boxes for firewood. These family records will introduce our children and their children to the young Ysabel.

After discovering his long-lost collection of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle action figures, Alex morphs into Donatello. “Cowabunga! I just found my life from age 8 through 10. These go into my vault.”

“What vault?” Ginger asks.

“Dunno,” he says, “Guess I need one.”

From a box of photos spirited from Ginger’s parents’ attic into ours a quarter century ago, Alex dusts off a framed photo of Ginger’s Dad on the ship that won him the Medal of Honor.

“Can I take this one for my wall?” he asks. After receiving the okay, he announces, “Maybe we need to slow down just a little. There’s good stuff in here.”

Apparently, for the past quarter century, we’ve unwittingly been living in an off-site storage facility of the National Archives. Haste in sifting through our living remains—and those of our forebears—would be foolhardy after all these years of earnest saving. Perhaps this separation anxiety is an unavoidable aspect of holding onto our stuff for dear life because they represent chapters of our lives and of those who came before us. Like Ysabel’s journal, which had been hiding in our attic for 25 years before we noticed it, much of what we’re discovering seems to have surreptitiously sought asylum under our roof.

I hear Ginger say, “How long do we need to keep my mother’s high school scrap books, and my grandmother’s recipe files, and that hideous ironwood rostaman you and Emily bought at a flea market in Jamaica 20 years ago? Pick it up. Hold it. Does it give you joy?

I know we face many iterations of letting go of stuff. We need to have conversations with our children about how our lives are evolving even while theirs evolve. We need to present, little by little, the souvenirs—the relics—we would like them to value. We need to recount our stories—and the stories passed on to us—in hope they can come to share the love.

Over time, Ginger and I will learn how to unburden ourselves. Even as we do, we’ll still get to visit and hold in our hands some of life’s souvenirs that we’ve handed down or passed off. And someday, she and I will kiss for the last time. First one, then the other—we’ll finish unburdening ourselves. And then, the joke’s on us: we too will become relics!

For now, I’m focusing on “making time go slow” while deciding what to add to my sock drawer. Actually, I’ve added a second sock drawer. Sorry, Alex.

After retiring in early 2015 from public health research, Jim Ross jumped back into creative pursuits after a long hiatus to resuscitate his long-neglected right brain. Since then, he's published 6 poems, over 25 pieces of nonfiction and over 90 photos in 30 journals, including 1966, Cactus Heart, Cargo Lit, Change Seven, Cheat River Review, Entropy, Friends Journal, Gravel, Lunch Ticket, MAKE Literary Magazine, Meat For Tea, Memory House, Pif Magazine, Riverbabble, and Sheepshead Review. Forthcoming: Bombay Gin, Palooka, and Papercuts. Jim and his wife are parents of two nurses and grandparents of one-year-old twins and a two-week old. They split their time between Maryland and West Virginia.